Naturally, anything we imagine about the future may turn out to be embarrassingly incorrect. The author is fully aware that he may make a fool of themselves, as so many others have before while attempting to predict the future. Even some of the most intelligent engineers and scientists have made predictions that turned out to be grotesquely inaccurate, sometimes within just a few years. Here is a brief, but easily expandable, list of some of the most notable failures:

"The Americans have need of the telephone, but we do not. We have plenty of messenger boys." - Sir William Preece, Chief Engineer, British Post Office, 1878

"Rail travel at high speed is not possible because passengers, unable to breathe, would die of asphyxia." - Dr. Dionysius Lardner, 1830

"There is not the slightest indication that nuclear energy will ever be obtainable. It would mean that the atom would have to be shattered at will." - Albert Einstein, 1932

"I think there is a world market for maybe five computers." - Thomas Watson, chairman of IBM, 1943

This clearly illustrates that even some of the smartest people failed to predict developments in their own field of expertise that were just around the corner.

To better understand the difficulties of predicting human development, it makes sense to distinguish two fundamentally different factors that can disrupt predicted trends::

Totally random, external events such as the earth being hit by a massive meteorite or the arrival of an extraterrestrial species.;

Much less random, but still difficult or perhaps impossible to predict, impacts of human actions.

The first category of events, which are entirely beyond our control, are cosmological catastrophes that can happen at any time. For instance, the sun might have exploded three minutes ago for some unknown physical reason, and we could all evaporate in five minutes. Or, a meteorite as big as Manhattan might be on a collision course with Earth and could hit us three months from now. Although these events can occur tomorrow, they typically occur over time-scales of hundreds of thousands or millions of years. In other words, their probability of occurring is "smeared out" over a very long time. Even if there is a high probability that the Earth will eventually be hit by a massive meteorite, it would be really "bad luck" if it happened within the next 1,000 years (Cotton-Barratt, 2016).

The second category of unpredictable events has a much shorter time scale. We make decisions today that will significantly impact the course of human affairs over the next 100 years. Consider climate change! If global climate is indeed influenced by our CO2 emissions (as most researchers believe), our decisions over the next 10 to 20 years can either accelerate or slow down global warming and significantly impact living conditions within just a few generations. In fact, American journalist David Wallace-Wells has argued that climate change could lead to devastating environmental, social, and political conditions within the lifetime of a teenager living today (Wallace-Wells, 2017).

The unpredictability of the future does not solely stem from totally random external events. Rather, it largely depends on our decisions and actions, which are often poorly understood. The future is unpredictable because we, as humans, are unpredictable.

We have demonstrated a remarkable propensity throughout history to abruptly change course. Consider some of the recent political events: Virtually no one had foreseen the collapse of the Soviet Union and the unification of Germany, not even a few months before they happened. Hardly anyone could have imagined that the United States would elect a reality TV host with dubious political expertise instead of a former First Lady and seasoned politician as President. Observers were in disbelief when the results of the Brexit referendum showed a clear majority in favor of separating from the European Union. And many Germans were surprised by the wave of welcome that some of their fellow citizens offered to refugees and migrants from the Middle East, turning their relatively closed society into a symbol of a multicultural immigrant society almost overnight.

If the future depends on human decisions and actions, we must strive to better understand which actions are easier and which are more difficult to predict. Upon examining past predictions, it becomes clear that those most frequently were proven wrong that predicted specific technologies or scientific discoveries. However, predictions about human behavior, social structures, and demographic trends were often surprisingly accurate. This is not because they were inherently better predictions, but because much less has changed in social relations than in the technical world.

Consider the Greek tragedy, a form of theatre that reached its pinnacle in Athens in the 5th century BC. It often describes human behavior that hasn't changed much in the past 2,500 years. In fact, Greek tragedies often tell stories of human relations that could easily happen in our time. That's one of the reasons why we still perform them in theatres today.

Or consider some of the basic insights concerning the organization of political affairs. The "res publica" of ancient Rome (503 BC to 27 BC) describes most fundamental political processes that we can still find today, including conflicts, betrayals, corruption, propaganda, and many forms of government oppression. Principles of state organization, administration, and law that were defined more than 2,000 years ago are still in existence today. Today's legal systems in Europe are often directly based on "Roman Law."

My father was born in 1903 in a small village of Eastern Europe. He often told me about his own childhood - how he had to get up at 4 am in the morning, how he lit a candle to wash his face with ice-cold water from a pitcher on his night stand; how he walked down to the kitchen for breakfast. It was a cozy place close to the wood fire in the stove on which his mother had prepared eggs, malt-coffee and hot milk. He told me how his father came in with his storm lantern which he needed for milking the cows. After breakfast my grandfather saddled the horse and he and my dad rode to school - my father sitting behind his dad on the horse back. My father's first task at school during winter was to bring in wood for the classroom's woodstove. After school my father walked home for almost 2 hours. In the summer he often helped the farm hands make hay which he liked a lot, because he could sit high on top of the hay bales when they took them to the barn with a horse-drawn cart.

As a small boy I couldn't hear enough about this strange world of my father's, where they had horses, candles, firewood and where they were milking cows with their hands.

My father died at age 84. When he was a small child he had seen the first car coming to his village; he had watched the first Zeppelin and later the

first double decker airplane. He had been witness to the electrification of their village and he had seen one of the first electric light bulbs

light up in his part of the world.

But on July 20, 1969 at 20:18 UTC I sat together with him and my mother in our living room and watched on TV the landing of the lunar module Eagle on the Moon.

Imagine this: within only 66 years, my father had gone from the candle-technology of lighting to the technology of a TV-broadcast of the first Moon landing.

In less than a lifetime, technology had evolved from the invention of the combustion engine to the implementation of rocket technology for a space ship.

I have little doubt that we will see equally breathtaking technological development over the next 100 years. We will see technologies, we cannot even dream of. When my dad saw the first light-bulb in his parent's house he certainly could not imagine (and no one could) that his son would sit in front of a computer linked with a worldwide digital network through a laser beam in a glass-fiber cable.

Despite this breathtaking technological change my generation still lives in a social, economic and political world which is not totally different from that of my father. We still have families, eat breakfast and go to school. In both our worlds we have wars, economic competition, poverty, wealth. There are powerful people and those that are suppressed. We still have to learn a lot and work hard to make a living. We still have ambitions and search for love and companionship. I am sure, the generation of my daughter will have the same basic challenges and dreams and a social and political environment that will not be entirely different from what we have today - or the environment that existed 1,000 years ago. However, what will certainly change beyond our most outrageous expectations is the technological environment in which these basic social, economic and political structures will be embedded. This analysis will try to focus on those basic structures and how they might evolve over the next 1,000 years.

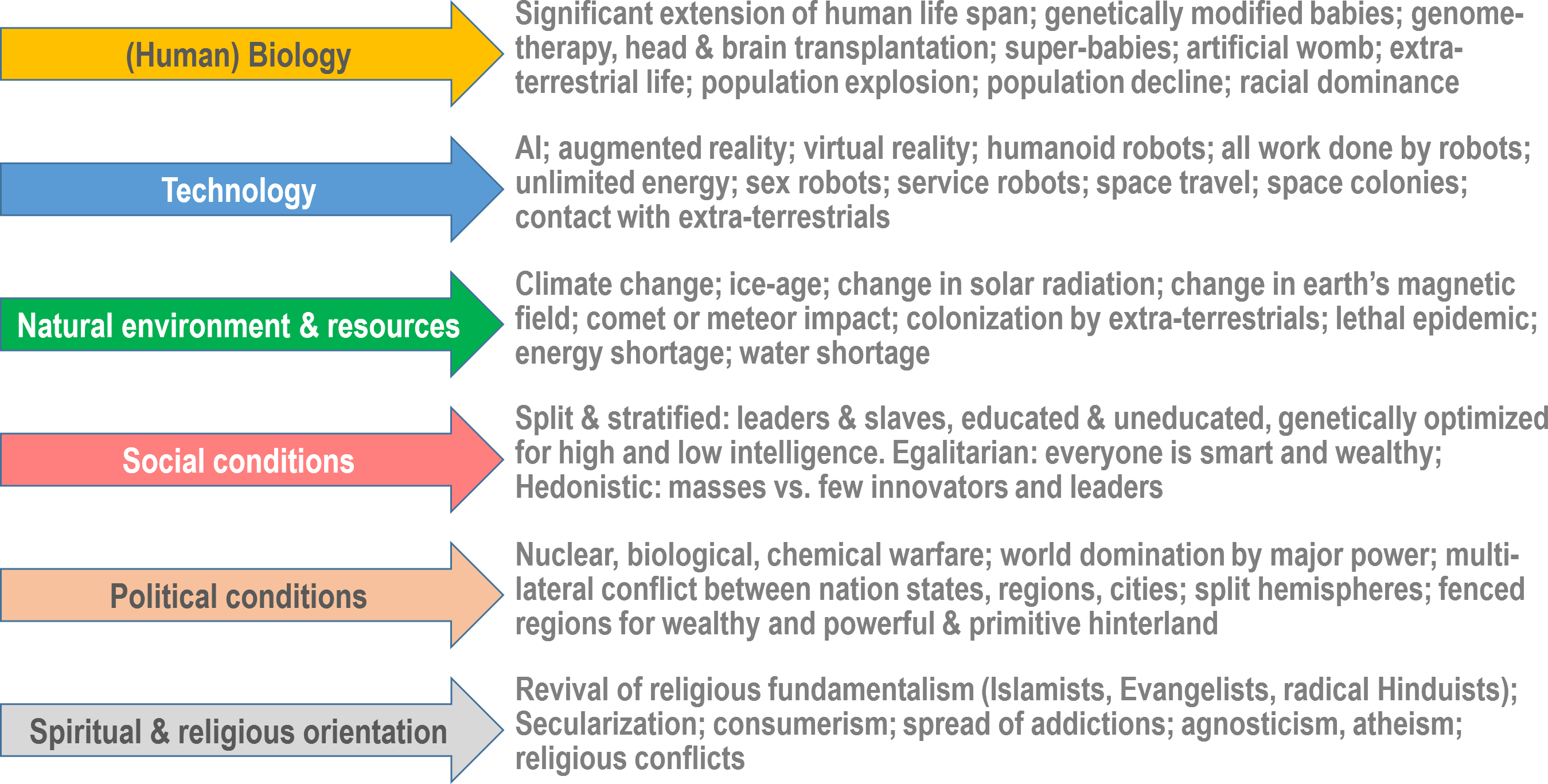

For that purpose we will imagine four types of future civilizations (see World 1 to 4) and consider how they might shape any of the following six basic dimensions of human life (see Diagram 1):